NOTES BY NORSE: Albany is a smaller town next to Berkeley in the East Bay. Activists, artists and houseless residents there have been struggling to continue to use the Albany Bulb. Street Spirit, one of the monthly homeless publications in Northern California, has described this struggle, and I reprint some of their articles below (the first article is from East Bay Indymedia). Street Spirit can be accessed on line at http://www.thestreetspirit.

Drug war rhetoric and policies seem to be returning with the rise of groups like Take Over Santa Cruz, The Clean-Them-Out Team, and Mayor “Rattlesnake” Robinson’s incoming regime. Troubling as well is the movement of formerly pro-homeless activists like Steve Pleich to the right, perhaps to regain a position of political credibility (in the eyes of the new homeless-ophobic authorities) –See https://www.indybay.org/

In spite of the passage of the repressive Robinson-backed Public Assembly constricting laws at the last City Council meeting of the year, plans for an permit-free DIY (Do It Yourself) New Year’s parade are reving up as usual for this time of year (See http://www.lastnightdiy.org/ ).

There are also some rumblings of concern among liberals and activists about the impact of freezing weather on the twice-the-housed homeless deathrate and talk about talking about a “warming center”. Whether this leads to any action is yet to be seen.

Thursday Dec 12th, 2013 9:37 AM

12.12.13 – A personal account of direct defense of people’s homes on the Albany Bulb on December 10th. This action comes shortly after Bulb defenders built rock barricades to halt police from entering the Bulb, a squatter community and autonomous space known for its art and sculptures made out of the former landfill.

The supposedly empty camp has a sign in the door reading “This camp is not abandoned. –Kris S.” Disregarding this, the police walk in and call to the city workers to follow them upon determining that no one is inside. The house is built into a tree on the side of a hill and is almost invisible until you stand in the entrance, from which you can see a set of stairs leading to the main platform, a storage area to the right of the entrance, and various belongings tucked away under tarps within the ground-scraping canopy of the tree. “There’s nothing of value here” a worker calls out. At this point it began to become clear that these workers had successfully repressed any signs of compassion or understanding for the lives of Bulb residents, as it was clear that there were belongings in this dwelling that had value to its residents. The police push me back as I attempt to get a better video of the camp, informing me that I have to give them space to do their work. As is typical of these situations, the cops and city workers repeat the ‘just doing our job’ mantra each time we challenge the legitimacy of their actions.

As the workers and police confer on how best to tear down this tree structure, a barefoot man walks up the path behind them. “I’m moving up into the treehouse so I can tear my camp down,” he tells the cops. A brief back and forth between the resident and one of the police officers ensues: “Well, they’re going to tear this camp down.” “That’s my stuff in there; I left a sign stating that the camp is not abandoned.” In typical underling fashion, the officer dodges responsibility: “The lieutenant is arriving, talk with him.”

A tense conversation between Kris, the Bulb resident, and the Albany Police lieutenant ensues. Kris maintains that the previous residents of the camp gave him permission to be there and that he has spent the last several days moving his belongings into the camp. The lieutenant insists that the camp is going to be demolished, stating “You have the opportunity to gather your belongings. That’s where we stand.” Kris stands barring entrance to the dwelling as the police demand his full name and date of birth. I stand at a distance filming until Kris calls out, “You can come in, you don’t have to stand where they tell you.”

I have never met Kris before, yet the simple fact that I am filming and questioning the legitimacy of the police has created some degree of trust between us. Entering the house, Kris gives us a tour and explains his experience of the escalating harassment of the Albany PD against Bulb residents. The previous night he had been stopped and ticketed for a supposed lack of lights on his bicycle and the officer had warned him not to violate curfew at the Bulb—despite them being a mile from the Bulb entrance. The house itself is a platform built up into a tree, with a domed roof made from a parachute which lets in light while keeping tree debris and water out. One wall has a built-in bookshelf and carpets cover the wooden floor. A housekeys not handcuffs sticker is prominently placed on the wall near the front entrance.

The police walk toward the entrance, so we go down to ensure they can’t come in. The lieutenant again tells Kris that the camp will be demolished and to get his stuff out. Kris insists that the previous residents of the camp gave him permission to be there and demands to see the paperwork the lieutenant claims releases the city to destroy the camp. The lieutenant finally agrees to show paperwork and heads to his unmarked car; Kris goes to put on shoes and warmer clothes.

Unfortunately Kris does not return. In his absence and above our protests, the city employees bring the dumptrucks and begin loading them up with the contents of the camp. They attack the tree with chainsaws, cutting a gaping hole into the canopy as they tear apart and remove the treehouse platform. Indiscriminately throwing personal effects, a bathroom bucket, and remnants of the demolished house into the trucks, they take the destroyed remnants of the camp to the large dumpsters up the road. As I film, a comrade sends texts and calls others: an alert to come help slow or halt the process.

As I stand watching the workers casually destroy this home, I wonder how they can possibly perform this task without a crushing sense of guilt at taking away the best shelter available to someone who has nowhere else to go. Many Bulb residents have pets or other factors which make them ineligible for the extremely limited housing resources offered by the city as the ‘cover our ass from lawsuits’ portion of the plan to sterilize and yuppify the Bulb. Most find the prospect of leaving the homes they have built and occupied for years in favor of three-month ‘transitional housing’ unattractive. The injustice of kicking people out of their space, alongside the love we share for the art and community enabled by the autonomous nature of the bulb, has caused a network of activists to coalesce in defense of the bulb and in solidarity with its residents.

Within two hours of our initial call-out, approximately thirty people have arrived. As soon as we numbered more than five, the decision was made to block the dump truck from continuing to haul items from the camp. Standing in a circle in front of the truck, the workers at last showed a shred of humanity in their decision not to simply run us over (an act that I would not have put past them considering their disregard for the basic right to shelter). To my surprise, the two police officers kept their distance and did not attempt to make us move. In typical anarchist fashion, we took the opportunity to hold a spontaneous meeting and discuss our plan. Consensus is reached almost immediately on the point of preventing any more camps from being destroyed, regardless of any police claims of release from the residents. Especially in the coldest part of the year, we agree that it is absurd to allow shelter which could be utilized to be destroyed.

More Bulb defenders arrive, including the legal team. A news van drives up and parks next to the police. As our numbers grow and the dumptruck is turned off, a couple of us take a walk toward the entrance to see if more police or city workers are arriving. We find a Waste Management truck coming up the road, bringing yet another dumpster for the use of City workers. To our dismay, after dropping off the empty container the truck positions itself to haul away the full dumpster containing the rubble of Kris’s dwelling and his personal belongings. I approach the driver of the truck and politely inform him of the situation, stating that I can’t let him take the dumpster until Kris has had a chance to retrieve his belongings. He walks off to consult with the City workers, and returns with the typical mantra: “I have to take this to the dump. I’m just doing my job, you would do the same in my position.” After we respond strongly that we would most certainly not do the same, he informs us that he will run us over if we attempt to block his truck.

Rallying a few people, we climb up into the dumpster in the hopes that it will prevent him from hauling it up onto the truck. Others work to open the back end so that trash will fall out if it is hauled away. Once it is opened and people are stationed on top of it, the worker gives in and tells us he will call his boss to declare an unsafe work environment. Although we later heard city workers planning to pick it up the next day, a small victory was won in that people were given a chance to retrieve their effects.

Other Bulb defenders inform us that negotiations regarding the second camp that was slated for destruction have resulted in the resident will be left alone to pack up her belongings and move them, which was her initial request that morning that the police had declined. We head down the low road and have another assembly.

After the meeting, the dump trucks returned yet again: A line formed along the entrance to the low road to block them from entering. A couple cops pull up and take a video but do not approach us; clearly they had not planned on encountering resistance and the two officers who did respond were unprepared to deal with our human blockade.

While Monday was far from a victory, seeing that a home was destroyed, the bonds of solidarity formed through the events and discussions which have taken place in the past months were called upon and a meaningful response occurred. The fact that within an hour of the call out well over two dozen people were present and acting directly in opposition to the continued dismantling of the residences shows that the City’s plan to destroy and sterilize the Bulb is being met with determined, ongoing resistance that will only grow as connections are strengthened and actions carried out.

From Fireworks: http://fireworksbayarea.com/

Comments

( runningwolf.zachary [at] yahoo.com ) Friday Dec 13th, 2013 10:58 AM

An iconic image of the Albany Bulb at sunrise. Grim, one of the campers, sang, “My country ‘tis of thee,” as he waved a tattered flag in honor of a land of the free, and the campers who fight for their homes and their rights. Robin Lasser photo

An iconic image of the Albany Bulb at sunrise. Grim, one of the campers, sang, “My country ‘tis of thee,” as he waved a tattered flag in honor of a land of the free, and the campers who fight for their homes and their rights. Robin Lasser photoby Robin Lasser

The Albany Bulb is a decommissioned construction dump with world-class San Francisco Bay views, friendly campers, and significant art and architecture. Standing on a windy bluff atop Mad Mark’s castle, you can see the Golden Gate bridge directly to the west, the Port of Oakland to the south, Richmond oil refineries due north, and Albany (notorious as the city with no housing for homeless people) due east.

The mudflats that form the base of the Albany Bulb migrated from the Sierra Nevada, residue from the gold rush when hydraulic gold mining unleashed sediment delivery from rivers to the San Francisco Bay. In 1963, on top of dreams of gold, a construction dump was born and the human-made spit of land took shape, adorned with cast-off piles of re-bar and cement slabs, along with marble from Richmond’s demolished City Hall and Berkeley’s former library.

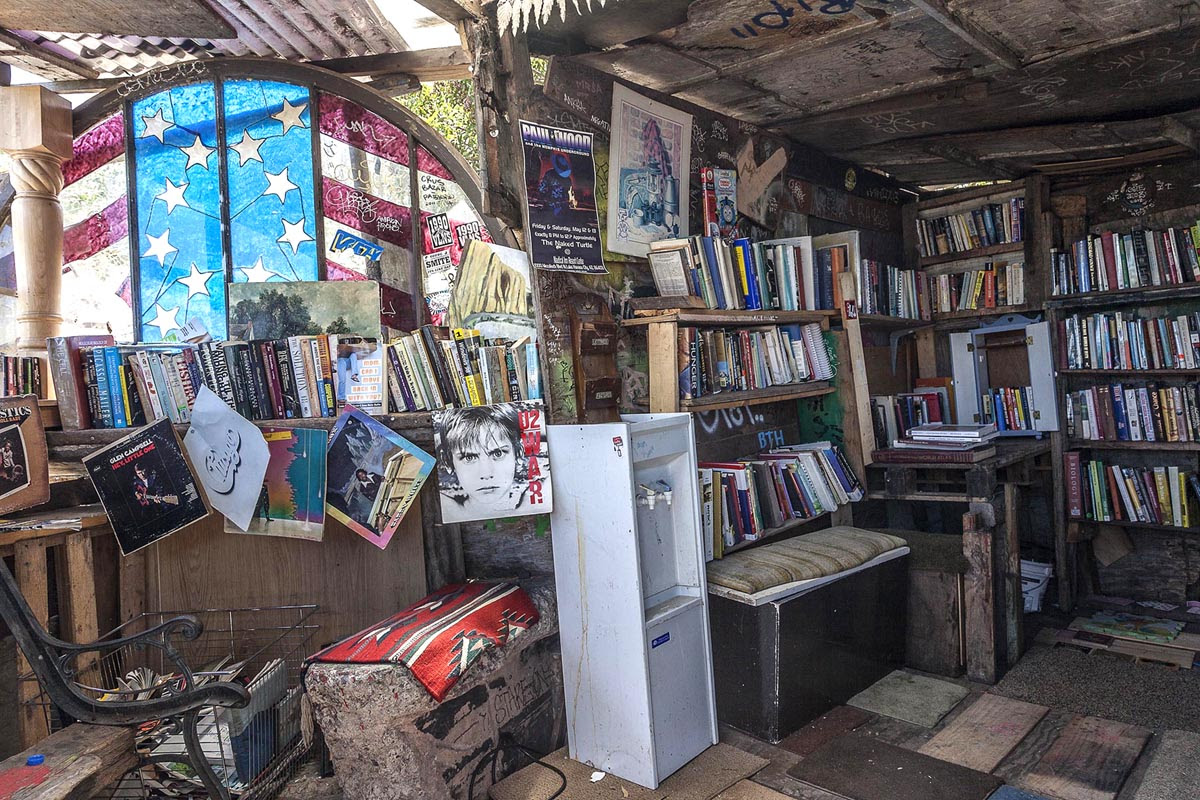

Today, the Landfill Library, created by Jimbow the Hobow and Andy Kreamer, resides on the northeast side of the Albany landfill. You can check out the book of your choice, utilizing the honor system for return. One filmmaker called this place, “Bums’ Paradise.” I have grown to think of it as home away from home.

The Landfill Library, created by Jimbow the Hobow, allows Albany Bulb residents to check out any book on the honor system. Robin Lasser photo

The Landfill Library, created by Jimbow the Hobow, allows Albany Bulb residents to check out any book on the honor system. Robin Lasser photoDefinitely put the Bulb on your bucket list, but don’t wait too long to visit, as the times they are a-changing. More than 60 campers are slated for eviction.

The Bulb is slated to become a park, but as one camper, Mom-a-Bear, eloquently declared in a recent Albany City Council meeting, “We already have a world-class park” — no need to make a new one.

The Bulb, for me, is one of the last stands in America where creative anarchy rules. And by that, I mean that the plants are wild, the art dotting every square inch of the peninsula is unsanctioned, and the residents embrace an alternative lifestyle. These elements seem to be in harmony with one another and it seems to be working.

I am a kindred spirit roaming the Bulb for almost two decades. I think this dump is the jewel of Albany, a vital destination point. The upcoming eviction will be a great loss not only to 60 or more residents who call this landfill their home, but to all of us who feel it is important to explore untamed territory, the boundaries between public and private space, and the intersection of people, art and ecology. How can I consider myself an environmentalist if I don’t also take into consideration human justice?

I began filming at the Albany Bulb for the purpose of documenting some of the ingenious ways some of the residents created homes. I am a professor of art at San Jose State University and I live in Oakland, California.

For the past decade, I have created, along with collaborator Adrienne Pao, nomadic, wearable architecture that we call “Dress Tents.” Imagine a 15-feet tall lady wearing a dress that you can walk into and utilize as a tent, a gathering space to consider the geopolitics of people and place. I wanted to explore how residents utilized recycled fabrics in their tent creations. I admired how residents at the Albany Bulb created home, physically and in terms of community.

Eventually, I began to talk more deeply with some of the residents. What turned the tides for me was something resident Stephanie Ringstad shared about camping at the landfill.

“Living out here is considered homeless, although we consider it our home,” Ringstad said. Her message hooked me and I refocused my lens on a fiercely alternative group of people living creatively amongst ruins littered with art, architecture, and wild plants.

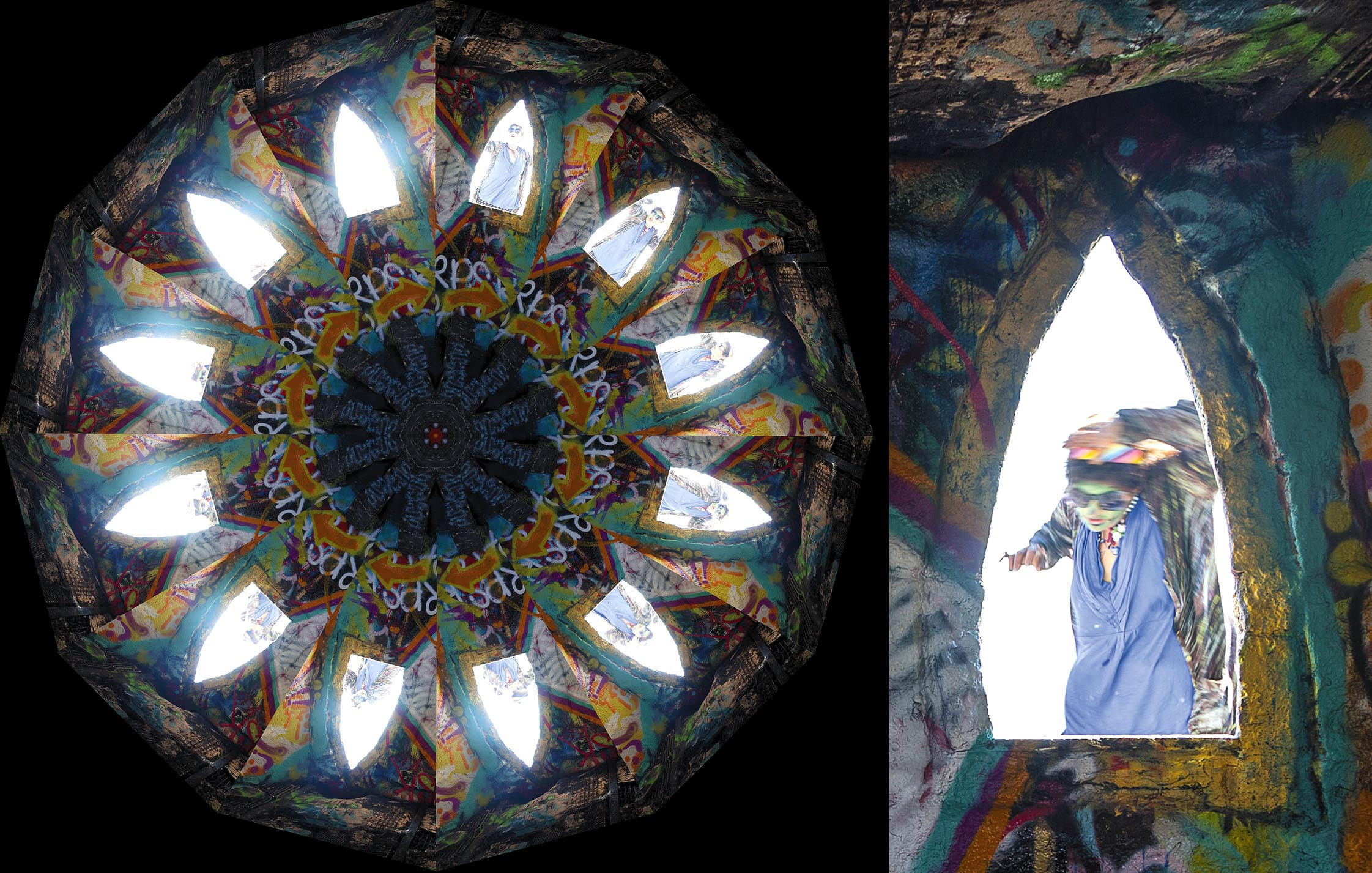

This mandala was created by Robin Lasser and Judith Leinen as is an image of Albany Bulb resident Tamara Robinson as she expresses her feelings of invisibility in a society that marginalizes the homeless by crying out, “I am melting.” The full mandala is shown at left, and the close-up detail at right shows a profile of Tamara as it appears in the mandala’s windows.

This mandala was created by Robin Lasser and Judith Leinen as is an image of Albany Bulb resident Tamara Robinson as she expresses her feelings of invisibility in a society that marginalizes the homeless by crying out, “I am melting.” The full mandala is shown at left, and the close-up detail at right shows a profile of Tamara as it appears in the mandala’s windows.Some portraits published in this story take on the form of mandalas. The word “mandala” is Sanskrit for whole world or healing circle. The mandala is a representation of the universe and everything in it; it is the most basic form in nature.

German artist Judith Leinen and I create these mandalas to honor the residents of the Bulb. They are a meditation on and celebration of the myriad ways residents use their creativity in response to life on the brink of change. The mandalas also serve as zoetrope image portraits.

Zoetrope means “wheel of life.” A Zoetrope is a device giving the illusion of motion. When spun on a disc, powered by citizens riding a bike made from metal scraps gifted to us by campers at the Bulb, these still portraits in the round come alive. The animations reveal creative actions by residents who in time of crisis choose to live creatively by painting, performing, cooking and community organizing.

The following stories of four women campers at the Albany Bulb are direct quotes transcribed from the feature-length film currently in production. The film is made in collaboration with campers who share their creative lifelines and stories in the face of changing tides. The accompanying exhibition is created in collaboration with my colleagues: Barbara Boissevain, Danielle Siembieda and Judith Leinen, along with Bulb residents.

In this article I am honored to highlight four courageous women campers. There are more than 60 residents living at the Albany Bulb that I would like to introduce, given the space. I would need volumes to do real justice to this extraordinary place and the individuals who have made this landfill not only their home, but a significant destination point brimming with vitality, culture and spirit.

It is here in this article that my voice ends and the extraordinary voices of Amber Whitson, Danielle Evans, Tamara Robinson and Katherine Cody begin.

Yours in the intersection of art, ecology, social justice and everything wild!

Amber Whitson, a seven-year resident of the Bulb, is an organizer who works with great dedication to preserve this community. Robin Lasser photo

Amber Whitson, a seven-year resident of the Bulb, is an organizer who works with great dedication to preserve this community. Robin Lasser photoAmber Whitson

Amber Whitson loves her home at the Bulb and works day and night, doing everything within her power to keep her home, and at the same time help others. Amber also serves as the narrator and humanities advisor for the developing documentary film and exhibition we are creating about the Bulb. Interviewed at her home at the Albany Bulb, Amber said:

“Home is called home for a reason. It is home base; it is where your heart and soul are. We put our blood, sweat, and tears into this little piece of land we call home. My biggest dream is just to live out my days here in peace.

“I know I have lots of days left. I am only 32 but I don’t think that is so unreasonable, especially with all the work I do out here for the community and the amount of persecution I have gone through. They stole my son; they did all kinds of horrible stuff. They jailed me, put me in a mental institution for 24 hours before the doctor wouldn’t keep me there saying, “You do not belong here you are not crazy.” I know that, but tell them that.

“Winters are getting harsher and winds are getting stronger. The weather in general is strange — global weirding. If there are going to be environmental changes happening, it is probably going to hit us first because we jut out into the Bay. If it is going to get ugly, it gets ugly here first, but that doesn’t mean that I wouldn’t want to live here. When there was that Tsunami they came out here with the fire department and a megaphone on top of their truck saying, “Everybody please evacuate to higher grounds.” What please? I just stayed in my backyard at a table in my shop and kept working. If I were to die, at least I know that I would have died in my home.

“I have a friend out here that is dying and he did not want to live anywhere but here either. As April said, “It is a dying man’s wish.” He said, “No, if I were going to have a wish, it would be for world peace or something.” Shit. But who could blame him for wanting to live where he is comfortable? He likes it out here. He calls it “the one place people won’t fuck with you or steal your shit even if you are homeless.” [Note: Pat died on October 17, 2013, at home on the Albany Bulb, surrounded by his family of friends and his dog Eva on his lap.]

“Now I am forced into getting ready to leave home behind, which is so weird. I don’t know how to be homeless. How do you compact an entire existence into what you can carry with you? You know, once you have an entire existence. Reducing everything to only what you need to survive.

This mandala was created was created by Robin Lasser and Judith Leinen in honor of Amber Whitson’s dedicated work to defend and preserve the community at the Albany Bulb.

This mandala was created was created by Robin Lasser and Judith Leinen in honor of Amber Whitson’s dedicated work to defend and preserve the community at the Albany Bulb.“I eat so healthy now. Soon I will not be able to have a stove. I don’t even mind eating leftovers from dumpsters, I do it all the time out here, but it is going to be so different when we won’t have anywhere to live. The thought of being tethered to a town sidewalk, rather than our home here, is incomprehensible.

“They want us out of our homes because they are thinking about making this into a park, even though many of us have been encouraged to move out to the Bulb. You know, out of sight, out of mind. Now they want to make the dump into a park. Well, it already is a park. And then they wonder why I don’t want to be a part of society. Gee, I wonder.

“You would never catch me treating people like this: ‘You there, I want you out of that home I have allowed you to settle in for seven years because I may want to go and recreate there sometime, possibly, if you weren’t there, but if you are there, I definitely won’t ever want to go there and hang out.’ ”

Danielle Evans

Danielle Evans has become a painter during her residency at the Bulb. This creative outlet helps keep her “sane” in troubled times. Danielle’s paintings are featured in the documentary and exhibition.

Danielle said: “The paintings are my mood swings. I just go with how I feel and what my mind tells me to do. I paint when I am pissed off. I express my anger in the paintings. I started painting two months after we arrived here (at the Albany Bulb). To be honest, it is a little crazy living here sometimes. Some of the people around here are kind of nutty so I stay to myself pretty much and I paint.

“Following my dreams and getting out my feelings — I think that is what I am doing. It is weird, some of the paintings are coming from within. Something takes over until it is done and then I know it is where I want to go. It is a good way of meditation, it helps me to relax and to not hurt anybody or think evil thoughts.

“Painting makes me feel calm and saner. I am able to go to sleep with a relaxed mind, not all jacked up. If I don’t paint, I can’t sleep because of all the anxiety of what is going on. So, painting is good.”

Tamara Robinson says she feels “invisible” in a land that disregards her existence, simply because she is homeless. Robin Lasser photo

Tamara Robinson says she feels “invisible” in a land that disregards her existence, simply because she is homeless. Robin Lasser photoTamara Robinson

Tamara Robinson feels she is “not really alive.” She feels “invisible” to a public that disregards her existence, simply because she is homeless. Tamara speaks of life’s hardships and decides to dramatize the character of the Wicked Witch of the West at three distinct sites on the landfill. The film and exhibition highlight Tamara’s highly personal and yet very political landfill performances.

“I am nobody, really. I am just a 23-year-old ex-convict who is dying. I can dream all I want about being the Wicked Witch of the West, Elphaba. She was my favorite because, just like me, she was a person and the reason why she turned into the Wicked Witch is because of life and its horrors. I don’t even feel alive, just like a spirit roaming. I know I see people and people see me, but the way they make me feel by their quick judgment, I wouldn’t say I was alive or anything.

“I wanted to die and felt like nobody cared. Growing up, I had nobody. In the hospital after I had taken all my father’s medicine to kill myself, he left me sitting there with a goodbye as he drove off with his new wife and her family. He is cold-blooded. It is all about him. Some people join the service with the idea that they are helping somebody, but he went in with the idea of kill, kill, kill. He wanted to destroy other people for the power of doing it.

“Just like the City Council wants to make us feel like we are a problem here at the Bulb, but I have noticed people out here do more for each other than I have seen anywhere else. This may have just been a dump that nobody wanted, but we made it our home.

“I relate to Elphaba, how she got the way she was. She did not start off like that; she was forced into it really, just like some of us here. Some of us are forced into this situation. I am alpha in every situation and I will fight for our rights. Expressing myself with fashion, performance, and dance out here at the landfill gives me something to look forward to, it makes me happy, gives me hope.”

Katherine Cody is the resident cook at the Bulb. She works with great dedication and generosity to feed the homeless people who live at the landfill and her tent is the Landfill Kitchen. Robin Lasser photo

Katherine Cody is the resident cook at the Bulb. She works with great dedication and generosity to feed the homeless people who live at the landfill and her tent is the Landfill Kitchen. Robin Lasser photoKatherine Cody

Katherine Cody is the resident cook at the Bulb. Her tent is the Landfill Kitchen. Towards the end of the month, when money dwindles, Katherine feeds 10-15 residents in a day. Campers find daily food, friendship, and solace at the Landfill Kitchen. Katherine is featured in the film and we hope she will be willing to cook food recycled from dumpsters for the opening receptions.

“I have this tiny oven. I feed the hordes with Easy Bake Oven parts! I think we are the most wasteful nation on the planet. We throw away tons and tons of edible food every day and that is where I get a lot of the food to feed people. Well, some folks will buy food with food stamps and contribute, others dumpster dive and contribute. Certain folks have really little to kick in except what they can do for work. So they wash the dishes and take out the garbage. I am terribly spoiled in that way. If you learn how to cook, you will be spoiled because it is an overwhelming process for some people.

“I put a big chunk of my income into it because I am feeding people that cannot do anything about work for food. And then there is Sparky. Sparky has difficulties. One day he came to me and said, ‘I have a can of gold spray paint,’ and I thought, ‘Oh no, because a lot of people huff with gold paint.’ And he said, ‘I am going to paint gold stars.’ I went out the next morning with my dog and walked amongst the stars. And that’s pretty awesome.”

Former Bulb resident Kelly Ray Bouchard wrote an eloquent declaration on these white rocks that described the natural beauty of the Albany Bulb and the hopes of the people who call the landfill their home.

Former Bulb resident Kelly Ray Bouchard wrote an eloquent declaration on these white rocks that described the natural beauty of the Albany Bulb and the hopes of the people who call the landfill their home.The White Rock Manifesto

In 2012, a former resident, Kelly Ray Bouchard, wrote this prophetic, white-rock manifesto: “This landfill is made from the shattered remnants of buildings and structures that not so long ago were whole and standing, framed in concrete and steel, expected and intended to last. Now, through the concrete, grasses make their way. Atop the plateau, a eucalyptus drives its roots down through the cracks. Waves constantly erode the shoreline and wash out the edge of the road. And here and there, in sections leveled and cleared of rebar, our tents are hidden away. We live around and within the rubble. Live — not merely survive. Can you see how hopeful this is?

“The Bulb is not utopia. It is not free from strife and cruelty and chaos, but neither is anywhere else. It is flawed, but it isn’t broken and shouldn’t be treated that way. We, too, are flawed but not broken. So when the politicians start asking their questions and making their decisions, you can help insure that we aren’t treated that way. Enjoy the Bulb. It is yours as much as it is ours or anybody’s.”

FROM STREET SPIRIT–DECEMBER 2013 at http://www.thestreetspirit.

This remarkable sculpture was created by Osha Neumann and Jason DeAntonis at the Albany Bulb. Marianne Robinson photo

This remarkable sculpture was created by Osha Neumann and Jason DeAntonis at the Albany Bulb. Marianne Robinson photoby Terry Messman

The horizons seem almost limitless as we walk along with Osha Neumann and Amber Whitson on an Art Tour to view the wildly colorful paintings and striking sculptures created in recent years at the Albany Landfill. As we look at the towering sculpture of a woman on the shoreline, her arms outstretched to the horizons, the sun slips down beyond the hills in the west, forming an inexpressibly lovely, rose-colored painting in the sky.

Art above and art below — beauty in the heavens and on earth. Yet, the beauty of the Albany Bulb stands in stark contrast to the ugly, destructive actions taken by the Albany City Council, along with their unexpected ally — anti-homeless environmentalists who may see the natural beauty of the landscape but have proven unwilling to see the beauty of the human lives and remarkable artworks that have found a home in the midst of the debris and concrete rubble of this dumping ground.

For many years, city officials tacitly permitted homeless people to live on the Albany Bulb, and the police often directed homeless people to live at the landfill because there was no other refuge for unhoused people in Albany. Now, after the utter refusal of Albany officials for the past 20 years to build a single emergency shelter or a single unit of housing for homeless people, and after Albany failed for 20 years to fulfill its state-mandated requirement to file a plan to build affordable housing, the City Council has decided that the only solution to homelessness is the mass eviction and forced exile of everyone living at the Albany Bulb.

During our Art Tour, as the sun goes down over the shoreline, the horizon where sea meets sky seems to go on forever. And if the expanse of the far-off horizon seems limitless, the imagination that created all these artistic works also seems unbounded and free.

Wind over water

Like wind playing over water, the human spirit has come to this shoreline and found a place of freedom — freedom to live, to create art, to build imaginative little shacks that provide a safe haven.

Poor people in this society are often imprisoned in claustrophobic little boxes. Residents at the Albany Bulb have found the freedom to escape the wretched SRO hotels, the dangerous neighborhoods and the claustrophobic warehouses called shelters that poor people are sentenced to live in, as though they were prisoners.

Here, at the Bulb, they live in imaginative little sanctuaries built by hand and blazing with art, instead of being consigned to shelters where scores of strangers are crammed into faceless barracks with no privacy, no dignity, no freedom, and with every second of life regulated.

But if the horizons and the physical freedom seem endless, they are not. The horizons have shrunk and our society is clamping down on freedom. The upper-middle-class politicians on the Albany City Council would prefer that there were no poor people. That is precisely why they have deliberately refused to build any housing or shelter for their homeless citizens for all these years.

Now that the poor have shown the capacity to develop their own homes, the council must invent new crimes and cast them all into exile. Suddenly, an area that was literally a dumping ground becomes such a valued piece of real estate that the poor must be driven out.

Festival of Resistance

Given the many years in which homeless people were permitted and even encouraged to take up residency at the landfill, Albany officials have given no credible explanation as to why they are acting with such haste to evict 50 to 60 homeless people as winter approaches.

In a show of support for the Bulb’s residents, a four-day Festival of Resistance was held over the Thanksgiving weekend.

On Friday, November 29, Osha Neumann, an artist and attorney, and Amber Whitson, a leading organizer of the Bulb community, led an Art Tour down a green avenue of flowers, paintings and sculpture created out of driftwood, construction debris, beached boats, and other found objects on the shoreline.

The profuse paintings, sculptures and colorful homes created by Albany Bulb residents were illuminated in the surreal glow of a sunset that almost seemed programmed from on high to showcase the artistic creativity of the landscape.

As sunset faded into cold twilight, this outdoor art exhibit of sculptures and creative shacks revealed its other identity as a place of shelter for homeless people with nowhere else to go.

Neumann is a mural artist and sculptor who created several of the most striking sculptures at the Albany Bulb, working with his son-in-law, Jason DeAntonis. Neumann also spends many hours at the Albany Bulb in his other role as an attorney who is representing homeless camp-dwellers in their lawsuit against city officials for proceeding with a mass expulsion that Neumann said is an act of “cruel and unusual punishment” in violation of the Eighth Amendment.

Creative artworks dot the landscape at the Albany Bulb. Painted chunks of construction debris sit near a towering sculpture by Osha Neumann and Jason DeAntonis. Robin Lasser photo

Creative artworks dot the landscape at the Albany Bulb. Painted chunks of construction debris sit near a towering sculpture by Osha Neumann and Jason DeAntonis. Robin Lasser photoThe discovery of freedom

In an interview, Neumann explained his connections to both the natural beauty of the Albany landfill and the homeless people who have found a home here. Just as homeless people have found a refuge that allows them to live in freedom in an over-regulated society, so have artists found the freedom to create unlicensed and unregulated works of art at the Bulb.

This level of personal and artistic freedom is nearly an endangered species in modern America, and one day the sculpture Neumann created of a towering woman with outstretched arms in supplication on the shoreline may stand as a memorial of the freedom that has been lost.

“The Albany Bulb is a place that has been important for me for well over a decade now,” Neumann said. “I first found out about it when I was taken there by people I know who are homeless and were living in People’s Park and who had moved there.”

Jimbow the Hobow, one of the mainstays at the Albany Bulb who created its free library, told Neumann there were people who were making “absolutely amazing paintings” down by the shore. The anonymous group of artists called themselves Sniff and their highly imaginative paintings on walls and big chunks of concrete sparked Neumann’s own artistic impulses. He began making sculptures out of driftwood and gigantic pieces of styrofoam from a broken-up dock.

Neumann’s political commitment to homeless people living at the landfill has equally deep roots. In 1999, Albany officials evicted a large community of homeless landfill residents and destroyed their encampment — an act of destruction that still echoes in the minds of people fighting today’s threatened mass eviction.

Neumann remembers it clearly. “We tried to stop Albany from kicking people out with no place to go,” he said. “At that time, as now, they had set up a little portable shelter in the racetrack parking lot for 50 people to go into. Nobody wanted to go into it, and people never got the kind of support they needed to fight back, either legal or political. So they scattered. They were pushed out onto the streets, and many into very desperate circumstances.”

The 1999 eviction was all the more unfair because Albany is one of the very few cities in the Bay Area that has refused to build shelter or housing for homeless people, and its dereliction of duty seems all the more inexcusable when it deliberately attempts to force homeless residents to move to other cities.

Today, 14 years later, Albany has still failed to build a single unit of shelter or transitional housing, and it is currently being sued for not even attempting to update its Housing Element, a crucial part of a municipality’s General Plan.

Cities are required under state law to show how they plan to meet the need for affordable housing. The City of Albany was sued in October 2013 by Albany Housing Advocates because city officials have not updated its Housing Element since 1992, and missed deadlines in 2001 and 2009 for mandatory updates.

“Albany never had any housing,” Neumann said. “It never had a shelter, and it never had transitional housing. Nothing. It was one of those communities that thought of itself as the ‘Urban Village by the Bay.’ They didn’t think of themselves as the kind of place that had homeless people — and they could do that because the homeless people were safely out of sight on this landfill.”

A human dumping ground

The Albany landfill had been a dumping ground for construction debris, and due to the refusal of city officials to develop homeless programs, it became a dumping ground for human beings as well.

“The Albany police and other police would even direct people that they found in Albany who were homeless to go to the landfill,” Neumann said. “It was sort of the designated place for homeless people to go. So people went there and they made a community there. They built homes, and they lived in those homes, and they shared their lives together. They created a library, and all the networks needed for a successful community, and it was a place where they could be left alone.”

Unwanted, criminalized and discarded people were cast off to a dumping ground formed from unwanted refuse and debris. Ironically, the people who had been discarded created such an interesting and beautiful landscape that elitist environmentalists and city officials decided they wanted to seize the formerly unwanted dumping ground and destroy the community that had developed.

Neumann said, “People who could not live anywhere else or who could only live furtively, and in hiding, lived there in this beautiful place. And they had the solace of living in nature. They had million-dollar views there and they loved it. They loved nature, they loved the Bay, and they shared it with all kinds of other people who loved the landfill the way it was — for its wildness, for the fact that it wasn’t all controlled and tamed.”

In a society that abandons and banishes its poorest members, it was intolerable for city officials to realize that some of the homeless poor had found a rare degree of freedom and enjoyed those “million-dollar views” that normally are the exclusive prerogative of the wealthy.

People camped out on the shore at the Albany Bulb during the Festival of Resistance. Robin Lasser photo

People camped out on the shore at the Albany Bulb during the Festival of Resistance. Robin Lasser photoThe shelter as jail

One of the reasons that people cling so stubbornly to this landscape is because there is nowhere else to go, certainly nowhere as free or as beautiful. Homeless people are well aware that if they are evicted from the Bulb, their only alternatives are being warehoused in a shelter, being confined in one of the cramped trailers set up by the City of Albany, hiding in a back alley, or languishing in a jail cell at Santa Rita for one of the class-bound offenses that are only crimes when committed by poor people.

“There are 50 to 60 people living out there, many of them with significant disabilities,” Neumann said. “Many of them have serious physical health problems, and they are proposing to take people out of their homes, out of their community, and stuff 30 of them into these two portable trailers that they have set up.”

On November 22, the City of Albany opened two small, prefab portables at a cost of over $330,000 to shelter 30 people for six months. Neumann and several other attorneys joined with Albany Housing Advocates in requesting that the City Council drop its plan to spend $330,000 on portable shelters that would only house half of the Bulb residents in severely cramped conditions.

The attorneys pointed out that, after six months, the portables would be removed, all the people would be homeless again, and Albany would have spent the entire sum with no long-lasting benefit at all. In a letter to the City Council, Albany Housing Advocates showed how the city could spend the same amount of money on direct housing assistance and place Bulb residents in permanent housing. The council dismissed the plan out of hand.

For many, it was “déjà vu all over again.” In 1999, many homeless people had avoided the trailer-shelters, likening them to jail or an internment camp. In November of this year, Bulb residents and Albany Housing Advocates warned the City Council repeatedly that homeless people would not trade their freedom and their homes on the landfill for the confinement of oppressively regulated portable shelters. They were proven right when no one sought shelter in the portables in the first four days after they were first opened on Friday, November 22.

Neumann said that the inhabitants of the Albany Bulb are avoiding the recently opened portables, in part because they have even less room than most shelters.

“These are really cramped, uncomfortable places,” he said. “You’re regimented and forced into an enclosed space with people you don’t know. Many people out there are disabled and have serious issues with being claustrophobic. Many have very bad experiences with institutionalization. For this community that has been able to exist as human beings out on the landfill, to be forced into these sardine-can portables is very dangerous to their health.”

Two sculptures sit side by side, looking like “old friends sat on a park bench like book ends,” as Paul Simon wrote on the “Bookends” album. Robin Lasser photo

Two sculptures sit side by side, looking like “old friends sat on a park bench like book ends,” as Paul Simon wrote on the “Bookends” album. Robin Lasser photoLiving in a little box

Amber Whitson has lived at the Albany Bulb for several years and is a dedicated organizer who has worked tirelessly to help her fellow campers protect the encampment from expulsion.

When asked if she would enter the portable trailers, Whitson said, “Would any of these City Council members be willing to go live in a metal trailer or Berkeley Food and Housing Project shelter that has bed bug problems and is seismically unsafe since the Loma Prieta earthquake? No! Nobody else is going to want to live in a little box that you can only be in 16 hours a day regardless of your disability or not, and where you have to be watched over by a hall monitor the entire time you’re there.”

Whitson pointed out that when all the money has been spent after six months, the trailers will be closed and the homeless people will be cast away with nothing. “When they pack up the trailers and leave, we would be again homeless,” she said. “But we would be more homeless than we were before because they would have bulldozed our homes on the Bulb.”

People are being asked to give up their homes, their privacy and their freedom in return for a few months stay in a trailer. Many Bulb residents are in long-term relationships and would have to be separated if they sought shelter in the portables. Still others have deep emotional bonds with their dogs, and cannot bear to give them up, as required by shelter rules.

Neumann said, “Albany is setting up a situation where they’re saying: ‘Cram 30 of these folks into these portables. The rest of you, basically, go to hell, or go wherever you want, but don’t stay in Albany.’ ”

Cruel and unusual punishment

On November 12, a lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court by 10 Bulb dwellers and Albany Housing Advocates charged that Albany’s plan to evict people amounted to “cruel and unusual punishment,” a violation of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, and also a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The suit was filed by the East Bay Community Law Center, the Homeless Action Center and the firm of Kilpatrick, Townsend & Stockton.

At a hearing on November 18, U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer refused to grant a temporary restraining order that would have prevented Albany from evicting the camp dwellers. The lawsuit on behalf of the campers can still proceed.

Many homeless people from the Albany Bulb who attended the hearing were very disappointed with Judge Breyer’s ruling. Neumann said, “The people from the Bulb who were in the courtroom couldn’t understand that the judge seemed to be unwilling to prevent Albany from evicting them just as winter is coming on and in the middle of this season of holidays. It’s hard for people who are in touch with the real human realities of this situation to understand this ruling.

“Albany is taking them from a place of safety and community where they have been able to survive — and these are people who have not been able to survive very well out in the streets and the back alleys. That is all being taken away from them. What that means is that people are going to be out in the cold and very vulnerable.”

Neumann warned that allowing Albany to proceed with this eviction could take a serious toll on the health and safety of people who have nowhere left to go.

“Some of them are extremely vulnerable, people whose health and life may be at risk because of Albany’s actions,” he said. “Many people at the landfill have significant disabilities, mental and physical. Some have serious health problems, seriously compromised immune systems, some with mobility problems.”

Amber Whitson said that “when we had 62 people at the Bulb, there were 38 disabled people. Our population keeps fluctuating in size and variety, but there is a large number of disabled people out here — more than half. But they don’t care. They just want us out of their way.”

Does anyone really know what time it is? Clocks on the tree at Lewanda’s encampment. Robin Lasser photo

Does anyone really know what time it is? Clocks on the tree at Lewanda’s encampment. Robin Lasser photoOutrage at Sierra Club

Whitson expressed outrage that supposedly liberal environmentalists are pressuring city officials to expel homeless people from the landfill. For decades, the landfill was just a construction dump. But Bulb inhabitants have lived in relative harmony with nature, and as environmentalists became aware that homeless people were living amidst vistas of scenic beauty, they began to covet a land that had long been ignored as a dumping ground.

As Whitson pointed out, the Albany Bulb is a landfill, and as such, it is hardly Yosemite or Sequoia National Park. “It’s a dump!” she said. “It’s a dump that nature took over, and because nature took it over, the Sierra Club and Citizens for Eastshore Park feel they have a claim to it. But that’s just not how it works. It shouldn’t be how it works.”

Albany Bulb activists held a protest outside Sierra Club offices in Berkeley on October 11 to voice their outrage at the Sierra Club’s support for the eviction of homeless and disabled persons.

Whitson said, “The Sierra Club and Citizens for Eastshore Park are pressuring and prodding and urging the council to kick us out of our homes for the environment, regardless of what the reality is. They’re spreading propaganda, and they just want us out of our homes. It’s not right.”

Neumann said, “One of the things that is really troubling is that some of the main instigators pushing the council in this direction have been so-called environmentalists. I think it’s an awful form of environmentalism that pits the poorest human beings against the environment. The reality of it is that if you look at what has happened out there to the land, the reason why the Bulb still is green and verdant is because people are still living there. If you look at what they’ve done to the places where they’ve kicked people out, they’ve turned it into a desert, they’ve clear-cut it.”

To add to the irony, people at the Albany Bulb are living more in harmony with the environment than most of our affluent society. They are not part of our consumer culture of massive consumption.

“If we are setting the environment against the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable of us, then we’re going to be in real trouble,” Neumann said. “Because the fact is, it’s the people out on the Bulb who are showing us how we’re going to need to live. They’re the ones who are living with the light carbon footprint, not us.

“This incredibly rich society does not provide the resources for people who are desperately in need, and here is a place where people are supporting themselves. It doesn’t cost a dime to the City of Albany, yet even that is being taken away.”