Identifying Potential Sites of Campgrounds for (Homeless) Members of

The Public: A Quest for Humanity on the Streets of Fresno, California

By Paul T. Jackson

T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s

Prologue

Formulation of a Legal Solution to a Legal Problem

Liability with Respect to Third-party Conduct

Liability with Respect to Water on Proposed Campgrounds

Liability with Respect to Use of Fire on Proposed Campgrounds

I. Along the East Side of Regional Sports Complex: Proposed Campground for Semi-autonomous, (Homeless) Members of the Public

II. 93721 Heavy-industry Corridor: Proposed Campground for (Homeless) Members of the Public with Mobility Issues

III. 93706 Light-industrial Corridor: Proposed Campground for Campers Who Are Bicyclists, Electric Wheelchair Users and Addicts

Conclusion

Prologue

For many years now, local churches, masjids, synagogues, and temples—their members impelled by a desire to reduce suffering in the homeless communities of Fresno, California—have raised funds to purchase fire-and water-resistant tents. So have conscientious, albeit agnostic residents in this city. Such tents are vitally necessary to the lives of homeless people, and are to be the only form of shelter in any campground the City will permit on the proposed public campgrounds to be discussed in this paper.

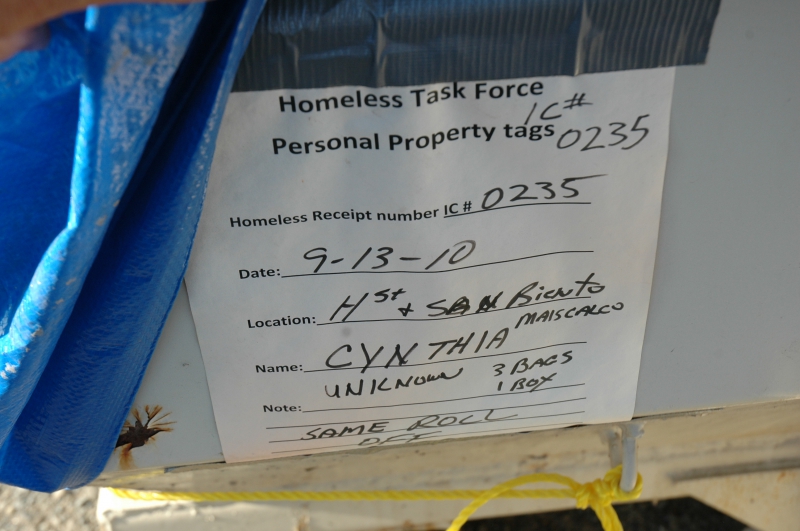

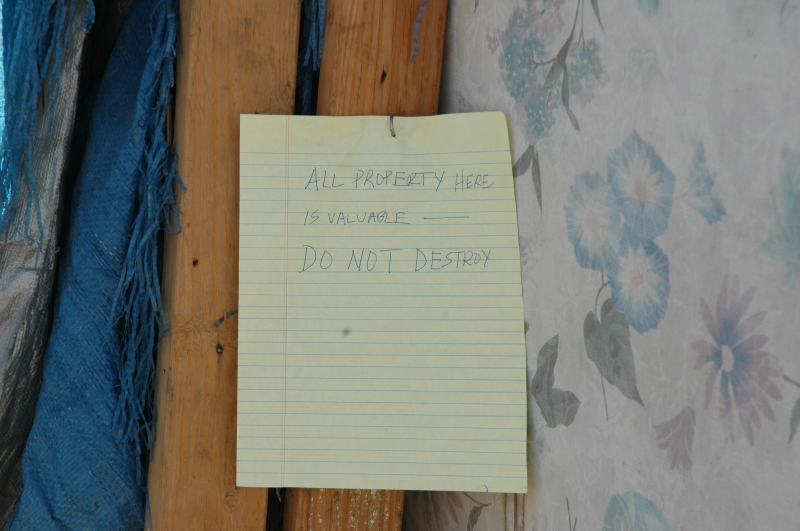

However, without assurance that, after the tents are set up, neither the City nor any other public entity will declare a “cleanup” only to tear the tents down and store them in bins virtually inaccessible to the owners of the much-needed tents awaiting alleged abandonment thereof, the religious, spiritual, and just plain decent impulses to live and let live would be imprudent. Our modest efforts to alleviate such needless suffering in our community would be frustrated by a City impelled by alleged concerns of health and safety necessitating abatement of each and every homeless encampment under the terror of the City’s territory, including even that which had been set up near the grain silos where concern for neither health nor safety appeared to anyone yet on this past October 23rd suffered the fate of all other woebegone people who, though lacking customary homes, seek to keep body and soul together. They seek to survive, despite the edict of some less-enlightened, if not benighted institutions whose leaders have the audacity to declare them to be mere street people or “infidels,” allegedly alienated from the dignity which we know to be inherent in every natural person.

Now, therefore, we have come to realize that definite steps must be taken so that our efforts to alleviate such suffering will no longer prove vain; that tents and sleeping bags purchased with hard-earned money for the health and safety of homeless people undoubtedly living harder lives do not end up forever lost to their owners as a result of measures allegedly taken for their health and safety; and that the people who need these donated items may use them safe and secure in the knowledge that the land on which they do is legally available to them under reasonable conditions and not a labyrinth of rules and regulations, such as are imposed at one facility housing some two percent of the local homeless population, while the remaining 98 percent endure waves of officially sanctioned repression.

Formulation of a Legal Solution to a Legal Problem

Since solutions concerning availability of land to those people who truly need it, must come through the legal system, it is self-evident that solutions will be wrought in that system. If traditional politicking—letter-writing, lobbying, petitioning, and picketing—were enough to bring about the necessary land reform, it would have been achieved long ago in an area with plenty of food and land to share.

We know solutions to homelessness must exist in Fresno, land-poor though the city is. The area is very rich in land and the foods grown here. Land, food, tents, and sleeping bags are primarily what the homeless people here need. If the City would but open public lands to the public—a seemingly obvious proposition—caring, socially responsible residents will see to the other three needs. A reasonable legislative body will open public land as a campground if furnished with unlocked bathrooms with running water for rinsing one’s hands, a duty of personal hygiene which most of our homeless wouldn’t shirk if given the chance, and if not entirely forgotten after having been locked out of public bathrooms downtown for so very long. With the bathrooms and dumpsters that will be made available to them, the living conditions of homeless individuals will satisfy the “health and safety” requirements of which local public politicians and officials drone in their attempt to justify “cleanups.” And a court of law could find a campground with these basic amenities of hygiene satisfies those requirements, often cited by those officials, though by means never the officials intended: Unimproved public land opened as a campground for (homeless) members of the public!

Most homeless individuals in Fresno, California need access to public services which are delivered downtown. Selecting the location of a proposed campground is usually made with that consideration in mind. Though land is plentiful, vacant public land is not. Selection of potential sites, which the writer makes using the City’s website (

http://gis4u.fresno.gov/viewer/), is a quest for all of the prerequisites the City must satisfy to use the law empowering it to open unimproved (or vacant) public lands; to avoid schools and parks incurring opposition to a proposed campground; and of course to choose location where it’s possible for us to enable (homeless) campers to meet the basic necessities of life.

Liability with Respect to Third-party Conduct

Criminality among homeless individuals has recently been documented and reported in The Fresno Bee. It’s sure to be the hue and cry of those local politicians who will oppose any proposal of the Fresno Homeless Advocates that the city open a campground. Generally, the City, as any public entity, is not liable for injury resulting from third-party conduct, whether negligent or criminal, on unimproved public land opened pursuant to chapter 2 of the Tort Claims Act. (See, e.g., Gov. Code, § 830.2 and § 835.)

However, in opening public lands as campgrounds for (homeless) members of the public, the City incurs liability if it’s reasonably foreseeable that a person will use property adjacent to public property (or the property itself) with due care, yet the person’s use results in danger due to a condition which exists in conjunction with some particular feature of the public property. “If the third party’s negligence or criminal conduct is foreseeable, such third party conduct may be the very risk which makes the public property dangerous when considered in conjunction with some particular feature of the public property.” (Swaner v. City of Santa Monica (App. 2 Dist. 1984) 150 Cal.App.3d 789, 804 [198 Cal.Rptr. 208].)

The City, by erecting a barrier on the perimeter of a campground, addresses its said liability if it takes a precaution against a motorist who (using due care) tries to make a U-turn crossing into a proposed campground or negligently crosses into it. The barrier need not prevent any possibility of a large truck from entering one of these proposed campgrounds. However, it must be so constructed as to make entry thereinto by a motorist an act of negligence entirely on his part, and not the City’s. It must be high enough above ground level and present a vertical face to the average motor vehicle that would alert any responsible motorist he is violating the boundary of the street and putting life and limb at risk.

Additional study is necessary to determine the specifications of the barrier.

In virtually all other conceivable cases, the City is immunized under Government Code, section 835 for any injury resulting from third-party conduct.

Liability with Respect to Water on Proposed Campgrounds

Access to potable (drinkable) water will remain a challenge for occupants of a proposed campground. Such water is not furnished in all wilderness areas, governed by the same law (ch. 2 of the Tort Claims Act, contained in Cal. Gov. Code, §§ 830—840.6) as that under which public land will be opened within our city limits. Where potable water is not available, a bathroom faucet may be set to produce only a trickle of water for cleaning one’s hands, discouraging its consumption and satisfying the minimum requirements of the Health and Safety Code.

We anticipate that occupants in outlying campgrounds lacking running, potable water will, at least over the short term, demonstrate the self-reliance, resourcefulness, and cooperativeness of homeless people of former tent cities “cleaned up” or destroyed by the City. We believe that they’ll secure and replenish drinking water for their own communities.

Liability with Respect to Use of Fire on Proposed Campgrounds

“Fire rings” are shallow concrete basins, usually about 4 feet in diameter. (Historically, these were used on California beaches, both for recreation (bonfires) and cooking, though they’re now banned on most of the state’s 108 public beaches.) Barbecue pits tend to be deeper.

The California Fire Code is contained in Part 9 of Title 24 of the California Code of Regulations (

www.calregs.com). The San Joaquin Air Pollution District has jurisdiction to give prior approval permit any open burning under conditions stated in the District’s authorization (Cal. Fire Code, § 307.2.1). And if an open burning “creates or adds to a hazardous or objectionable situation,” the fire code official may order such fire extinguished (

Id., § 307.3).

To keep themselves warm in wintertime, homeless people would probably be happier with a fire 15 feet away, rather than 50 feet away from any structure. Generally, an open burning must be 50 away (Id., § 307.4). However, if built in an “approved container,” a fire may be as close to a structure as 15 feet therefrom (Id., § 307.4, exception 1).

Additional study is needed to determine the specification of an “approved container.”

But if the pile size is 3 feet or less in diameter and 2 feet or less, the fire must be at least 25 feet away from a structure (Id., § 307.4, exception 2).

“Open burning, bonfires, recreational fires and use of portable outdoor fireplaces shall be constantly attended until the fire is extinguished. A minimum of one portable fire extinguisher complying with Section 906 with a minimum 4-A rating or other approved on-site fire-extinguishing equipment, such as dirt, sand, water barrel, garden hose or water truck, shall be available for immediate utilization.” (Cal. Fire Code, § 307.5.)

Selection of a campground may require consideration that a fire may create a hazardous or objectionable situation on certain lands. The first of three proposed locations could produce such a situation, requiring further study.

I. Along the East Side of Regional Sports Complex: Proposed Campground for Semi-autonomous, (Homeless) Members of the Public

Just to the east of the Fresno Regional Sports Complex are three large tracts of vacant land, presumably publicly owned. Their current use is actually non-use; they’re vacant. The City’s current plans are to use them as an open space/regional park, which would be adjacent to the sport complex.

With respect to the intersection of S. West Ave. and W. Annadale Ave., the tracts are on three corners, excluding the SE. The tracts to the NE and NW of the intersection span almost as far N as W. Jensen Ave. The tract on the SW corner is about half the area of that on the NW corner of that intersection. All three tracts are remote from residential parcels.

As vacant land without landscaping, buildings, or other improvement, these appear to qualify as “unimproved public land” within the meaning of California Government Code section 831.2, so that “[n]either a public entity nor a public employee is liable for an injury caused by a natural condition” thereof. (Ibid.)

The Fresno Homeless Advocates may propose that the City leave all three tracts unimproved, except for the paving of roads, construction of bathrooms, and furnishing of dumpsters and access to sanitary (though non-potable) water. These public works do not “improve” the land such as would remove it from coverage by section 831.2, supra. But these public works furnish the land with the basic necessities of an overnight, long-term campground. The Fresno Homeless Advocates may propose that the City revise its plan accordingly.

Whole families will have the opportunity to come from local churches to visit this large campground. While parents serve and/or share food with needy campers there, children (under proper supervision) will use the sports facilities at the adjacent complex. Churches that now serve food in Roeding Park and that sometimes find they end up with excess food, will coordinate with others in Fresno’s religious community, so that food and potable water are served to meet people’s needs in both large parks. (The sports park is about 4 mi away from the Pov’.)

We anticipate these proposed campgrounds will comport with the City’s recent (Nov. 9, 2013) recoding of the nearby Running Horse property, now called Mission Ranch, for large-scale commercial farming. The presence of such farming implies the absence of residences and schools, which would likely incur opposition to the proposed campground.

However, a threat to the feasibility of a campground on this tract appears if the vacant land, like the sports complex adjacent thereto, is reclaimed landfill. If so, methane emissions would appear to present a safety hazard to anyone using a controlled fire on such land, whether for cooking food, bodily warmth, or storytelling or other fireside recreation. The heat of a barbecue pit could raise the temperature of the soil on which it rests, possibly resulting in methane emission at dangerous levels. And if methane were emitting on hotter days of the year, any fire could present even greater risk to the public.

Further study is necessary.

II. 93721 Heavy-industry Corridor: Proposed Campground

For (Homeless) Members of the Public with Mobility Issues

Two vacant parcels lie to the S of the intersection of S. Cherry and S. Railroad avenues. The parcels are particularly helpful to those homeless individuals who have difficulty cooking for themselves, and/or mobility issues hindering them from walking long distances.

The parcels are only 0.6 mile away from the Pov’, an estimated 12-minute walk (or wheelchair ride). To the S of those two are three more, also in the 93721 ZIP code, i.e.: Parcel Nos. 28282828 and 23202320, both lying to the SW of the intersection of E. Florence Ave. and S. Tulip St. These are 1.1 mile away from the Pov’, an estimated 21-minute walk.

While constructing restrooms on all public campgrounds, including both of the parcels at Cherry and Railroad, the City would do well to furnish the two last-mentioned parcels with ramps leading to the restrooms. The City, as any public entity, is not required by the Americans with Disabilities Act to make every recreational area accessible to disabled individuals. But, to fulfill the ADA’s purpose of making public facilities equally available to disabled individuals, the bathrooms at the 93721 campgrounds should be furnished with ramps.

III. 93706 Light-industry Corridor: Proposed Campground for Campers Who Are Bicyclists, Electric Wheelchair Users and Addicts

In the 93706 ZIP Code, there’s a cluster of five parcels, all of which are listed as vacant land.

In the industrial corridor, no residential parcels or public parks are nearby. Nor are there any schools, the nearest being the Teocalli Dance Academy, which is 0.3 mile to the northwest.

The cluster of parcels has one which is fairly remote: A large parcel on the SW corner of the intersection of E. Church Ave. and S. Golden State Blvd. Just 0.1 mile to the west of that intersection is S. Sarah St.; on that street, 475 feet to the S of Church is Foundry Park Avenue, from which the same corner lot is accessible. Continuing 0.2 mile on Foundry Park Avenue (past Wilson’s Motorcycle), the said avenue comes to a fork: A 0.2 turn to the NE, connecting with Golden State, and the same avenue continuing SE another 0.1 mile to reach Ry-Den Truck Center at the cul-de-sac.

The four remaining parcels in the cluster are on either side of the 0.2 mile long avenue connecting to Golden State.

As vacant land without landscaping or buildings, these appear to qualify as “unimproved public land” within the meaning of California Government Code section 831.2, so that “[n]either a public entity nor a public employee is liable for an injury caused by a natural condition” thereof. (Ibid.)

Assuming campers have some means of transportation, they’ll have two services within their reach. The Turning Point G Street Residential Re-Entry Center is just 0.3 mile to the northeast, an estimated 7-minute walk on Golden State Boulevard. The proposed campground will be convenient for recovering addicts.

The Pov’ is 1.4 mile away—an estimated half-hour walk or ten-minute bicycle ride—mostly along Golden State Boulevard. Using this route, which is low traffic and also the shortest to the Pov’, campers will avoid the dance academy, which is the only public facility in the area.

Conclusion

In our quest for legally sustainable, politically suitable, and truly feasible solutions to homelessness, we are confronted by chapter 2 of the Public Tort Claims Act. This chapter contains laws permitting a public entity to open unimproved public land to the public. To provide a base of stability for Fresno’s harried homeless population, we propose homes be made available to them in the manner of a campground. Such a proposal appears the quickest for the great majority of the people and the least costly without jeopardizing life and limb, let alone the immorality of the City’s apparent war against homeless individuals.

To that end, we have moved that the Fresno Homeless Advocates propose the City open the above mentioned “vacant” parcels near downtown, and the large “vacant” tract three miles to the east thereof. To make our proposal legally and politically viable, we must see it through the City’s eyes. Therefore, we attempt to address liabilities arising if the City were to open the vacant (unimproved) public lands for our stated purpose. Whatever liabilities each location poses to the City, and whatever advantages each poses to the proposed campers, the writer hopes this paper has invited the Fresno Homeless Advocates to engage in serious thought into the kinds of considerations necessary to formulate a viable proposal that would alleviate the living conditions of our longsuffering homeless communities.

The author, Jessie Speer (center), with Ray Polk (left) and Larry Collins (right) at the H street homeless encampment, which the City of Fresno plans to bulldoze on Sept. 9.

The author, Jessie Speer (center), with Ray Polk (left) and Larry Collins (right) at the H street homeless encampment, which the City of Fresno plans to bulldoze on Sept. 9.

The City of Fresno destroyed Yellow Feather’s shelter and confiscated her property. She now sleeps on the sidewalk near the Poverello House.

The City of Fresno destroyed Yellow Feather’s shelter and confiscated her property. She now sleeps on the sidewalk near the Poverello House.

Rev. Dr. Chris Breedlove of College Community Congregational spoke at the press conference organized by homeless advocates

Rev. Dr. Chris Breedlove of College Community Congregational spoke at the press conference organized by homeless advocates