We tend to believe that wealthy countries like the United States don’t have informal settlements. Not only is this false, but it allows western governments to further marginalise an already misunderstood community. In the first of three articles on America’s informal residents, Martha Bridegam meets two residents of one such harassed community in San Francisco.

In August this year, city and state authorities in San Francisco raided a camp of makeshift homes under a freeway ramp and beside a commuter rail yard near the downtown area, destroying some residents’ property and evicting them from the site.

The San Francisco Chronicle‘s Kevin Fagan described the camp this way: ‘a sprawling mini-city of tents, suitcases and makeshift Conestoga wagon-style trailers, and a 50-strong homeless population that had been there for years. It was the biggest street camp in San Francisco.’ One resident has denied it was so large, but it was certainly substantial for a town that discourages group camps.

Residents were given 72 hours’ notice to vacate but some were offered and accepted temporary city-rented hotel rooms. The San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness (SFCOH), an activist group largely staffed by precariously housed volunteers, reported the eviction proceeded relatively respectfully but later posted complaints about promised rooms that didn’t ‘pan out’.

When thousands of Americans make the same housing decision, and stick with it through cold nights and police harassment, they can’t all be suffering defects of character or logic. For them, informal housing must be the best bad deal available.

Respectfully or not, campers who didn’t leave were ordered out. Some of their property was taken to maintenance yards for later claiming; some was destroyed, in part by workers wearing paper suits and masks. After the raid the camp re-formed, but smaller and under heavier weekly harassment. From past experience as a volunteer advocate for informal campers (in part through SFCOH) I expect the size of the camp may be ratcheted down over time.

San Francisco is dotted with small clusters of makeshift homes, especially under elevated freeways and in the remaining warehouse districts. The housing may be tents, shelters built around shopping carts, or vehicles, especially older recreational vehicles (‘RVs’, American English for ‘caravans’). Police and public works staff regularly disperse these unauthorised communities and destroy portions of their property as waste. The campers regroup. The cycle repeats.

I think our officials justify clearances of camps, and conventionally housed neighbours accept them, out of civic perfectionism. They presume informal housing can’t really be necessary, not in the prosperous United States. Taking comfort from the existence of government and NGO services for homeless people, they assume these services can meet all homeless people’s needs — hence that informal housing is a choice made by people who refuse to be helped.

They are proven wrong by the quiet ubiquity of makeshift housing in San Francisco and across the United States. When thousands of Americans make the same housing decision, and stick with it through cold nights and police harassment, they can’t all be suffering defects of character or logic. For them, informal housing must be the best bad deal available.

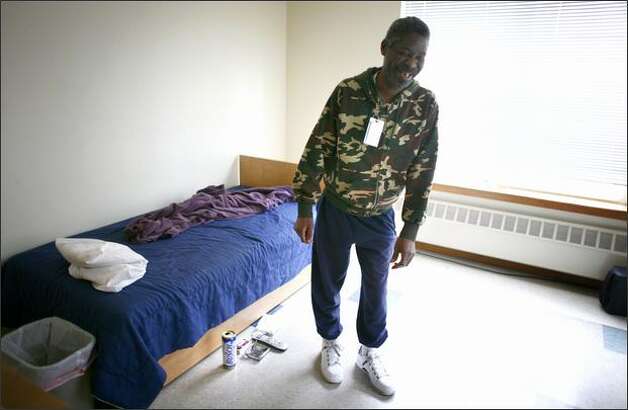

There are indeed chances to stay indoors. San Francisco’s aid program for indigent childless adults provides accommodation for up to 27 or sometimes 33 months, though many initial placements are in shelters rather than hotels. The program typically uses old-style downtown residential hotels built during San Francisco’s post-1906 earthquake recovery. Solid shelter despite the risk of crime, noise and bugs. To keep a hotel or shelter placement, though, residents must meet paperwork requirements, follow rules on matters such as dogs, clutter and visitors, and, in most cases, pursue either paid employment or federal disability benefits.

People easily fail or bolt out of that system. Other forms of subsidised housing have long waiting lists. The city’s nightly shelters, though disliked, turn people away regularly. That leaves informal housing.

Two residents of San Francisco

The Chronicle spoke of conventionally housed people as ‘residents’ but of informally housed people as ‘homeless’. That phrasing reflects an established asymmetry: campers may see conventionally housed people as neighbours, but property owners and neighbourhood associations tend to discuss campers as inarticulate elements of a category, ‘the homeless’.

City and Caltrans policies require property of value that is not abandoned to be stored for later claiming. But Sticks said, ‘they don’t give us no option. Whatever they take, whether it’s personal or what, it’s going to the garbage.’

When I visited the camp site in October the man who welcomed me was a lifelong San Francisco native. He introduced himself as Sticks (‘I shoot pool’). Now 56 years old, he said he had lived in the camp much of the past seven years. I asked him what people called it. He said, ‘we call it home.’

Highway workers had fenced off only one small camping area. Tents and shelters had returned, though fewer than in August. (Later I met more residents: some seasoned campers, some recently homeless.)

Sticks found the August eviction less worrying than the new severity of weekly sweeps by the state highway agency, Caltrans. One such raid had destroyed his own property. ‘They took all my clothes and everything and just put it in that big-ass truck that crushes everything.’ He meant a garbage compactor truck, the kind that breaks and compresses property and takes it to the landfill, beyond recovery.

City and Caltrans policies require property of value that is not abandoned to be stored for later claiming — rules reinforced this September by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in Lavan v. City of Los Angeles. But Sticks said, ‘they don’t give us no option. Whatever they take, whether it’s personal or what, it’s going to the garbage.’

For water and restrooms he said the camp relied on a public park nearby. It has an outdoor drinking fountain and an indoor restroom that closes overnight. Sticks said an unguarded tap nearer the camp had been shut off. Had residents asked for portable toilets or other amenities? He said, ‘we’ve talked to them about a whole lot of things,’ mainly through an ex-schoolteacher spokesman, but they claimed to be ‘having too many complaints.’

It’s a circular problem: there will always be complaints about crime and sanitation at an informal community if authorities approach these problems not as governance and civil engineering challenges common to every human settlement but as proof that the camp must be removed.

Sticks believed the harsher weekly sweeps were reactions to a series of maliciously set fires that followed the August eviction. Sticks and his friend Rashan, who joined us mid-conversation, said the fire-starter was not part of the camp: he was a resident’s bitter ex-boyfriend.

Rather than discuss guarding the community from further attack, Bevan Dufty, lead official on homelessness in the office of San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee, responded to the worst of the fires by telling the Chronicle, ‘an incident like this can make people more accepting of services, and it also sets off bells that this is not a safe place to live.’

Rationalising the eviction

Public rhetoric surrounding the eviction reflected support from a liberal-conservative consensus. Expressions of solidarity on the left and objections from the Coalition on Homelessness represented minority views.

Bevan Dufty is a popular liberal figure, formerly an elected member of the Board of Supervisors (similar to local council). Speaking to the Chronicle before the eviction, he portrayed the freeway camp as dangerous to its occupants and said city employees were reaching out to provide appropriate services and housing instead. He told the paper, ‘we’re going to say, “this change is coming and you need to think about what you want to do and can we help you figure that out.” The worst that could happen would be for 50 people to be kicked out onto the streets.’

A representative of the less liberal California Highway Patrol interviewed by a local television station spoke more bluntly: ‘mainly, it’s to remove garbage, excrement, rats, that kind of thing.’ A Caltrans spokesman told the Chronicle of plans to bar returners with a stronger fence. His comments were consistent with other Caltrans statements that portray ‘encampments’ as a problem of trash removal. (Caltrain spokeswoman Jayme Ackemann said the commuter rail system does not own or police the freeway camp area but does remove campers from its own land, offering services when it does.)

Right-wing anti-homeless messages bloomed in the Chronicle‘s online comments. One commenter used the rhetoric of addiction recovery, which holds the addict responsible for self-improvement: ‘Enabling the homeless lifestyle is not compassion. When you make it comfortable for people to be homeless, they will stay homeless. The cops need to be tearing out these homeless encampments as soon as they crop up. The only money we should be spending toward the homeless issue are [sic] in drug rehabilitation and psychological services. That way the homeless have two options: Get treatment or move.’

Learning from the developing world

Although unauthorised settlements have legitimacy problems everywhere, it’s inspiring to consider that in some parts of the developing world, informally housed people count as ‘residents’.

Rashan responded warmly when I suggested the freeway camp might elsewhere be understood and respected as a town. He mentioned people he had seen invoking squatters’ rights during his childhood in Jamaica. ‘They would just plant a little food and put up a little shanty or whatever they could use — bamboo or wood or whatever they find … not just thrown together, I mean, well-knit, you know, I mean, well done … some people just have to live like that, you know? And a lot of them had kids and stuff and their children were always the brightest in school, just, I mean, incredible, you know?’

In San Francisco I do think formally and informally housed people may yet learn to negotiate with each other as neighbours — not beloved neighbours, just neighbours who admit to sharing the same plane of existence.

As I’ll discuss next, hard times in the United States are drawing attention to informal housing. Some punitive raids and legislation have followed, but there’s also a current of sympathy, especially for newly homeless people living in their cars. With that, I think, comes hope for improvement.

COMMENTS at http://globalurbanist.com/2012/11/20/campers-of-san-francisco

The criminalisation of homelessness and informal settlements in US cities

Why do “squatters” in houseboats become residents, but campers in tents and caravans remain “homeless” and unwanted? In her second of three essays on America’s informal residents, Martha Bridegam describes a recent increase in criminalising legislation and policing against homeless and informally housed Americans but asks, is this a short-term backlash against changes in the nature of US housing?

One of several houseboats on Mission Creek in San Francisco. In the 1960s residents of houseboats were treated almost as squatters and threatened with eviction at short notice, as campers are today, but houseboat living is now viewed as a legitimate lifestyle. If attitudes towards these erstwhile “squatters” can change, could attitudes towards campers in tents and caravans in public space also change? Might camping one day no longer be seen as “homeless” but as a legitimate form of residence, however imperfect, and campers given the chance to stabilise and improve their liing conditions as houseboat residents have done? Photo: Joel VanderWerf

The United States has seen a recent striking increase in local laws and clearance campaigns against visibly “homeless” people — a category that, to Americans, includes residents of makeshift housing such as those I introduced here last month. Infomal shelters were not the sole targets of these campaigns but group camps and some organised “tent city” communities did suffer raids and removals.

Headlines about backlash measures suggested that poor people had become more visible as users of public space. On the other hand, with mainstream news reports full of no-fault misfortunes, such as evictions of foreclosed borrowers’ tenants, it seemed Americans might be attaching less moral blame to the loss of housing. There were hints of selective sympathy, especially for recently displaced people, those living in vehicles, and residents of orderly “tent cities”.

Campaigns against visible poverty

At that, Boden’s customary fluent profanity deserted him: he emailed a copy of a photo from a somewhat later Fresno demolition in December 2011. It showed men in paper suits kicking down makeshift plywood homes. Boden wrote, “Has she even looked at the HUD budget lately?”

As the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty (NLCHP) reported in 2010, uses of public space by homeless people have been contested for decades through criminalising legislation and civil rights litigation. Civil rights precedents on the use of public space require that arrests be made only for discrete prohibited acts, not for characteristics such as lack of housing that were formerly defined as “vagrancy”. To get around this, modern anti-homeless laws criminalise acts such as sleeping, sitting, trespassing (including sleeping in doorways), begging, drinking alcohol, erecting shelters, or sharing food.

But mid-2012 produced a special hail of punitive local ordinances and eviction sweeps against people described as “homeless”. In May the city of Denver passed an ordinance against camping on public or private property. Camping bans are common nationwide, but Denver’s ban was especially strictly worded and represented a sharp break from the city’s prior level of tolerance. It banned “eating, sleeping, or the storage of personal possessions” in conjunction with any “shelter” consisting of tents, bedding, or “any form of cover or protection from the elements other than clothing.” Although arrests had not been made under the law as of October, just its threat was said to be clearing usual camping areas, with homeless people being “driven underground“.

In June USA Today reported on a national trend of punitive ordinances: the Denver law, talk of public space restrictions in upscale Ashland, Oregon, and a Philadelphia ban on food sharing programmes in parks — a ban defended in let-them-eat-cake style by Philadelphia mayoral spokesman Mark McDonald: “We think it’s … much more dignified … to be in an indoor sit-down restaurant.” From the Tampa Bay Times: laws were passed against sitting or lying on sidewalks and rights of way in parts of Clearwater, Florida.

San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors passed a law prohibiting the parking of large vehicles on specified streets, ironically including some where inhabited RVs (caravans) have traditionally been herded by police. (A friend has described her first-hand experience.) Nearby Berkeley came close to passing a ballot measure in imitation of San Francisco’s largely unenforced 2010 ordinance against sitting or lying on the sidewalk, but the proposal was narrowly defeated in the left-tending November 2012 election.

Formed in the 1960s, the houseboats along Mission Creek have outgrown a past semi-squatter status that at one point saw an abrupt threat of 30-day eviction notices. It’s now viewed as a chic bohemian enclave with no questions asked about residents’ trustworthiness…

California’s state highway agency, Caltrans, demolished camps in the towns of Vallejo and Los Gatos. In Sacramento residents have been evicted from generations-established campsites along the American River, in one case displacing approximately 150 people. A “cleanup” campaign on Los Angeles’ notorious Skid Row included both much-needed waste disposal as well as destruction of campsites, sometimes including arrests.

But the September court ruling Lavan v City of Los Angeles, which arose from property destruction in prior Skid Row raids, presented a major advance by protecting campers’ rights to possess “unabandoned” property left on the sidewalk, though the city still can and does dismantle campsites. And this October, activist attorney Mark Merin won payments for 1,143 past residents of Sacramento encampments who lost property in evictions dating back to 2005.

Compassionate demolition?

At the national level, responses to criminalisation vary substantially and, surprisingly, by agency. At the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), spokesman Brian Sullivan chose words carefully about local measures directed at homeless people. He said he didn’t know if HUD had a policy on “sanctioning” or on “depopulating camps”, but “the law enforcement approach doesn’t answer the fundamental question about how are you going to house homeless people”.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) contributed to a recent report on alternatives to criminalisation but has also funded a policing think tank, the Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, that provides an intelligent but prejudice-skewed guide to removing “the problem of homeless encampments“. It presumes that camps pose crime and safety hazards by and to “transients” and must be removed.

Given that the US Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) participated in the report on avoiding criminalisation, it was surprising to see the mayor of Fresno, California quoting approving comments from USICH director Barbara Poppe in a press release about a November 2011 camp removal.

The statement attributed to Poppe apparently responded to local officials’ assurances that many displaced people had been or would be housed. It reads: “I applaud the City and its partners for focusing on the housing-first approach to addressing this issue and getting the public, private and nonprofit sectors aligned to services and housing to the men and women living in the encampments … The City and its partners have shown true leadership in energizing the community to respond in a way that is compassionate to individual needs and also makes sense for the greater community.”

I heard about Poppe’s comments from Paul Boden of the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP), who headed the San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness when I volunteered there as a lawwyer. He told me USICH confirmed the quote and provided further material from Poppe saying in part: “The costs associated with trying to ensure the safety, health, and well-being of people in encampments would be more strategically spent on housing.”

At that, Boden’s customary fluent profanity deserted him: he emailed a photo showing men in paper suits kicking down makeshift plywood homes (see photo gallery). He wrote: “Has she even looked at the HUD budget lately?”

That is, Poppe’s comment presumed it is possible to get all campers into conventional housing — except it isn’t. As Boden and WRAP point out persistently, HUD spending on housing construction and subsidies has been steadily far below the level of need since the cuts of the 1980s.

The man who took the demolition photo, homeless-rights campaigner Mike Rhodes, writes that Fresno authorities and NGOs have created some housing meant for homeless people, but nowhere near enough. During late 2011 his activist Community Alliance Newspaper chronicled an especially heavy series of multi-site demolitions in which bulldozers destroyed residents’ structures and property. He wrote to me about Fresno authorities: “They see providing any public services to the homeless in these encampments as helping them to live in these degrading conditions, therefore they refuse to help.”

Why the sudden visibility?

“Tent cities” became discussed as a rising US trend as long as three years ago. The National Coalition for the Homeless reported extensively on West Coast examples in 2010, calling them “America’s de facto waiting room for affordable and accessible housing”. Meanwhile its Twitter feed (a source for several items reported here) has been monitoring the nationwide backlash — including for example a Talent, Oregon, report about a sudden “homeless problem“.

Homelessness isn’t new since the global financial crisis. It had a long remission in the US from the Great Depression of the 1930s through the 1970s but substantially reappeared in the 1980s with the Reagan Administration’s cuts in social support programmes. It became institutionalised a quarter-century ago: July 22, 2012 marked the 25th anniversary of the federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, the first federal law to dedicate major spending to homelessness, though it spends less than was cut from welfare and housing programmes.

City populations are now presumed to include a stratum of unhoused and underhoused people, described as “homeless”, circulating among weekly-rental hotels, shelters, subsidised housing programmes and campsites. Homelessness is understood as a condition of life, even a quasi-ethnic social status or, in the case of “chronic homelessness”, a housing status elided with medical diagnosis.

What is new is that homelessness has overflowed into public view from a system of services that, while they didn’t end homelessness, managed for a generation to partially contain and routinise it.

Waiting rooms or living rooms?

It is beginning to seem optimistic to view informal communities as “waiting rooms”. Moves toward legalisation of makeshift housing are already appearing as cities admit to the need. Unfortunately, some combine substandard conditions with the paternalism of traditional US shelters.

Rhodes is a long-term critic of one such complex in Fresno, Village of Hope, run by an NGO called Poverello House. It provides sleeping space in tool sheds without utilities. His 2004 photos of closely spaced sheds behind a wire-topped fence induce a slight shudder. Poverello House’s website states the village is self-governing but Rhodes has written that homeless people tend to dislike the strict rules, which include a requirement to leave the site in daytime.

Similarly, town governments have experimented with legalised parking “programmes” for RVs. One in San Luis Obispo is limited to “only those people who commit to case management and remain drug-free and alcohol-free.” In nearby Arroyo Grande the police reviewed applications for spaces in a small parking area.

The police chief of Nevada City, California, began to issue permits to sleep in public.

A few camps of the autonomous type are hanging on, offering valuable chances to prove that people without money have no special need to be told how to live. After many past evictions, the large self-governing Nickelsville community in Seattle is being allowed to remain at a site on appropriately named Marginal Way. However the organisation still seeks legitimacy. A resident said the community is allowed to contract for portable toilet and garbage pickup service but the city will not help with those costs nor provide utilities — yet city service programmes sometimes refer people there to stay. Last year the Seattle Post-Intelligencer found 130 residents including children and pregnant women.

In Sacramento, the uniquely sophisticated and reportedly democratic Safe Ground initiative seeks refuges for campers on both public and private land. It has drawn national and international human rights attention. Significantly, a news report on City Council skepticism toward Safe Ground led with the question: “Should a group of homeless people be allowed to camp together in Sacramento without outside monitoring?” Currently lacking a main campsite, the organisation continues to search.

Better, but more elusive, is the possibility that unauthorised communities could become regularised as neighbourhoods, with residents accepted simply as townspeople. A heartening model is available in San Francisco: the houseboats along Mission Creek, a frequently polluted but picturesque channel in the same urban renewal area as the freeway camp I’ve described previously. Formed in the 1960s, the houseboat group has outgrown a past semi-squatter status that at one point saw an abrupt threat of 30-day eviction notices. The community has become more conventional in legality and lifestyle over time. It’s now viewed as a chic bohemian enclave with no questions asked about residents’ trustworthiness, though the group had to campaign fiercely for a while to stay put amid development.

Unfortunately, the houseboaters are distinct from poorer residents of RVs who parked around that shore until gentrification drove them out. A recent article on the colony underscored the class difference between houseboat residents and RV campers by saying of the houseboaters, “until recently, they were the only people out there.”

As I’ll discuss further in the next article, it remains to be seen whether informal community legalisations can be a means for residents to escape the irregular, second-class status of “homelessness” or whether such places risk becoming institutional holding areas where people wait for a chance at conventional affordable housing.

In this third article on American informal housing, I’m glad to turn from accounts of a group camp’s

repeated decimation in San Francisco and of other

criminalisations of homelessness to more hopeful talk about progress eroding the all-or-nothing view of housed status that I earlier called “civic perfectionism”.

The visibility of informal housing in the US is a new factor that may reduce social exclusion of people defined as “homeless”. An archipelago of encampments has formed — “movement” is too definite a word — where residents are inching toward acceptance with conventionally housed neighbours.

Such acceptance is needed because Americans will not all be in formal housing any time soon. Those without it need recognition in the meantime as community members with their own goals and rights.

Feldman suggests Americans over-idealise the “proper home” and view the house-dweller as the archetypal solid citizen. Such nostalgic respect has a harmful side: it tends to make conventional housing a prerequisite for acceptance as a fully fledged person with rights, therefore defining “the homeless” as incomplete people without rights.

Homeless Sacer

Arguably informal communities reduce housing-based social exclusion by creating a visible middle layer of housing between reductive stereotypes of “housed” and “homeless”. The new prominence of “tent cities”, groups of cabins sharing washhouses or kitchens, or groups of RVs (caravans) parked together, can encourage a view of housing quality as a continuum from worse to better. The continuum approach keeps the focus on improving people’s real circumstances — what Jane Jacobs called “unslumming“. That’s healthier than the too-common official practice of destroying makeshift housing on the principle that it’s not good enough to be real housing.

I’ve drawn some of these thoughts from a post about Giorgio Agamben and American homeownership by Aaron Steinpilz and much more from political scientist Leonard Feldman‘s 2004 book Citizens Without Shelter: Homelessness, Democracy, and Political Exclusion.

Feldman writes that Americans have been taught, in ways that feel apolitical but aren’t, to see “the homeless” as victims or criminals, but not as political actors nor as townspeople. Drawing on Hannah Arendt, Agamben and others, he suggests Americans over-idealise the “proper home” and view the house-dweller as the archetypal solid citizen. He argues that such nostalgic respect has a harmful side: it tends to make conventional housing a prerequisite for acceptance as a fully fledged person with rights, therefore defining “the homeless” as incomplete people without rights. Campaigns for acceptance of informal housing are a way for people defined as homeless to claim the rights and social significance of “complete” people.

Legitimacy in tent cities

Tent cities and other encampments have made progress winning legitimacy, perhaps because the public now believes residents who say they have nowhere else to go. By living openly and unremarkably in informal housing, and appearing as civic participants in their cities, residents prove that “homeless” people are real Americans, not figures waiting to resume life as Americans if or when they return to conventional housing.

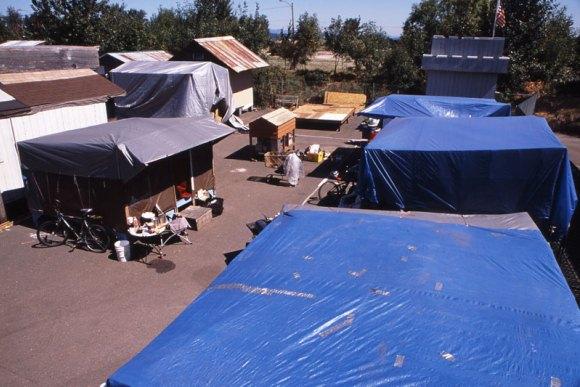

Mitch Grubic, elected CEO at the uniquely self-managed Dignity Village camp in Portland, Oregon, knows that potential. Having lived in his car, he understands the hassling and contempt. “That attitude of ‘omigosh, a homeless person coming into my neighbourhood, omigosh’ — I don’t know what it’s going to take for that attitude to change.” He said the subject comes up constantly in his community of 50 cabin-dwellers, which has contracted to use space on the edge of a city recycling yard. He said “we have game plans” to change public perceptions: to say “we are empowered people, we’re not what you think we are …

That’s going to come from the camps. The shift in paradigm is going to be coming from camps like us.”

By living openly and unremarkably in informal housing, and appearing as civic participants in their cities, residents prove that “homeless” people are real Americans, not figures waiting to resume life as Americans if or when they return to conventional housing.

Photojournalist Steve Wilson, who for five years has been documenting Dignity Village, calls some villagers “upper-class homeless”. He defines them as “those complete enough within themselves to succeed in America’s decades of ‘more than my share is my share’ but have opted out.” He wrote: ”Upper-class homeless’ are experimenting with minimalism: villages responsibly sharing, environmentally aware and self-governing by choice, not economic necessity.”

Grubic says many people in Dignity Village are around his own age of 50 and fed up with a society that rejects older workers and demands too much striving to reach a too-high standard of living. Their minimalism seems a virtue created by necessity.

Working tent cities aren’t utopias. The strongest ones enforce membership standards and conduct rules. Grubic imposes sanctions at Dignity Village, appealable to a resident council, ranging from one-day expulsions to permanent banishment. During our phone conversation he broke off repeatedly to judge a dispute: “Larry, you go back to the commons, Jerry, sit down, OK? … Don’t fight with him, OK? I appreciate it … Larry, let me just deal with it, OK?” He was promising to impose a 24-hour expulsion on a resident. “I’m gonna get him out of the camp. But you cool off too, OK? How about that?”

So nobody’s claiming to resolve the eternal tension of community versus individual rights. But at least tent city communities are starting to claim the equal protection of the laws: when police are called to Dignity Village, it’s not to arrest the group for camping, but to address a crime on behalf of the group.

Grubic spoke warmly of the possibility that US encampments might form a national organisation. It’s natural: they are starting to seem numerous and they’re starting to find each other. In this regard Grubic pointed out the work of Andrew Heben, a researcher and activist now working on the Opportunity Village project in Eugene, Oregon. Heben maintains an impressively crowded if not comprehensive wiki map of U.S. tent cities online. His online PDF book and web site, both titled Tent City Urbanism, build on the 2010 west coast tent cities report by the National Coalition for the Homeless to describe a nationally extending world of voluntary encampments and makeshift homes.

Plumbing as acceptance

To a surprising extent, encampments’ levels of acceptance are indicated by the infrastructure allowed to them. Even clean water is something not always offered to campers, since to offer water is to recognise that campers have a right to exist. Sanitation arrangements seem to represent the next step upward, then formal permission to remain on sites. With full utility hook-ups, an encampment is on its way to becoming a neighbourhood.

San Francisco provides many services to individual homeless people but does not directly serve informal housing areas except through antagonistic “clean-ups”. The park restroom pictured in my first article, a block from the freeway camp mentioned there, is comparatively one of the most convenient and welcoming to campers. It’s sad to remember that in 1998 the Vehicularly Housed Residents’ Association, assisted by SFCOH, nearly created an authorised parking area for RVs and other inhabited vehicles. It would have had a washhouse and formal self-governance; there were architectural drawings. Then apparent support evaporated at City Hall; the plan collapsed. (A local news feature conveyed the possibilities though it understated police harassment and offended several interviewees.)

This year, in passing a parking ordinance directed against RV dwellers, some members of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors (similar to local council) called for an authorised RV parking or storage area. However, the site suggested was remote Treasure Island; the purpose sounded like containment, not empowerment. Supervisor Carmen Chu told the San Francisco Chronicle, “Traditionally, vehicularly housed individuals have been very difficult to get into city services … We are hoping that this will get these people to them.”

In Sacramento, members of the Safe Ground Sacramento tent camp in 2011 secured a fact-finding visit from the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the violation of their human right to safe drinking water and sanitation. (I’ve discussed this on my own blog.) However, Steve Watters, director of the Safe Ground Sacramento NGO, said his group has given up assisting unauthorised tent camps because local elected officials would not stop the police from repeatedly evicting campers. Instead, the group is serving immediate needs with indoor shelter arrangements. Later members hope to create an authorised “transitional housing” site with solar-powered cabins surrounding a community centre with utilities.

Residents would stay one year. Ideally they would move up in life, but in case not, the group was struggling with “what do you do at the end of the year?”

Mike Rhodes, the embattled Fresno, California advocate I mentioned in previous articles, has managed to contract for portable toilets at camp sites without city objections. For six months he contracted for a Dumpster (skip) to remove residents’ trash regularly from one large camp. He says Fresno is unique in that camps tend to remain for six months to two years, sometimes with solid wooden structures, between city demolition campaigns. Rhodes is involved now, for at least the second time, in a federal lawsuit over such demolitions.

In Seattle, in addition to Nickelsville (also mentioned previously), the SHARE/WHEEL local NGO supports two tentatively authorised tent camps. Since my own past advocacy experience in San Francisco has involved frustrating efforts to protect formerly tolerated RV campers against gentrification, I’m glad to see academic researcher Graham Pruss winning respect and empathy for vehicular residents in Seattle, recently as lead author of an advisory report to the Seattle city government that explains hardships of vehicle camping from the inside and calls for “safe parking” arrangements in the city.

Dignity Village is one of several sites with groups of cabins. Residents have shared water taps, portable toilets, propane heat in cabins, hot water at central showers with authorised drain hook-ups, a computer room, electric coffeepots, and a microwave oven. Grubic regrets, however, that permits haven’t come through for a real kitchen: “We get low marks on cooking.” And he hopes for a better location: the current site gets leaf mould smells from the city composting facility and noise from the nearby airport.

Of course there’s always room to improve, to “unslum”. But it’s great to see these sites steadily improving conditions on low budgets without waiting for someone to raise the absurdly high costs of conventional subsidised “affordable housing”.

I have one more storehouse of knowledge to recommend on informal housing. Significantly, it’s the guide offered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to counting “unsheltered” people in HUD’s controversial “point-in-time” enumerations of homelessness. The document’s authors are required by laws and rules to define nearly everyone in informal housing as “unsheltered,” yet they provide knowledgeable introductions to cases that ought to be viewed as exceptional, some third thing other than “unsheltered” or conventionally housed: “snowbird” RV-dwelling retirees; the “off-the-grid” community in

California known as “The Slabs“; the “colonias” near the Mexican border, where houses are formally owned or rented but lack proper utilities; other substandard rural housing; trailers in rural areas whose residents count as “housed” or “unsheltered” depending largely on where they are parked with what level of

permission.

It begins to seem that official knowledge unofficially includes significant awareness of informal housing; officials simply need to bring that knowledge out in the open and admit that it concerns housing.

Other encouragements

Informal housing could benefit from a trend begun when the state of Rhode Island passed a Homeless Bill of Rights protecting, among much else, the right to exist and possess property and privacy rights in public space. WRAP is now campaigning for a recently introduced California legislative bill that would grant rights similar to the Rhode Island measure.

Another hopeful development is that Occupy encampments introduced middle-class demonstrators to homelessness in fall 2011 and 2012. As Barbara Ehrenreich explained, voluntary and involuntary campers together faced the hounding and property destruction that police use against the poor in ways viewed as apolitical. News reports suggested Occupy campers who had nowhere else to live were not real protesters — illustrating Feldman’s theory that homeless people are viewed as outside politics. Maybe fellow demonstrators learned otherwise.

There’s always danger that tent cities or parking areas could become places of enclosure rather than welcome. But it seems possible that democratic governance can emerge or persist in voluntary encampments.

The “homelessness” state of exception is an internal exile more populous than many US states. For most, the way out of this virtual prison isn’t past formal gatekeepers into formal housing, but by blurring the lines drawn around people called “homeless” — and that requires people inside and outside the lines to contest their absurdity. People are starting to do that. And in the process, more Americans may be recognising each other as neighbours.

While informal settlements exist in advanced cities like San Francisco, they often take very different forms to those seen in the developing world. Here, in a scene typical of the city, a small community of informal residents cluster their RVs–recreational vehicles or caravans–discreetly together under a freeway viaduct. Photo: Martha Bridegam

While informal settlements exist in advanced cities like San Francisco, they often take very different forms to those seen in the developing world. Here, in a scene typical of the city, a small community of informal residents cluster their RVs–recreational vehicles or caravans–discreetly together under a freeway viaduct. Photo: Martha Bridegam One of several houseboats on Mission Creek in San Francisco. In the 1960s residents of houseboats were treated almost as squatters and threatened with eviction at short notice, as campers are today, but houseboat living is now viewed as a legitimate lifestyle. If attitudes towards these erstwhile “squatters” can change, could attitudes towards campers in tents and caravans in public space also change? Might camping one day no longer be seen as “homeless” but as a legitimate form of residence, however imperfect, and campers given the chance to stabilise and improve their liing conditions as houseboat residents have done? Photo: Joel VanderWerf

One of several houseboats on Mission Creek in San Francisco. In the 1960s residents of houseboats were treated almost as squatters and threatened with eviction at short notice, as campers are today, but houseboat living is now viewed as a legitimate lifestyle. If attitudes towards these erstwhile “squatters” can change, could attitudes towards campers in tents and caravans in public space also change? Might camping one day no longer be seen as “homeless” but as a legitimate form of residence, however imperfect, and campers given the chance to stabilise and improve their liing conditions as houseboat residents have done? Photo: Joel VanderWerf Overlooking a corner of Dignity Village in Portland, Oregon. Photo: Steve Wilson/

Overlooking a corner of Dignity Village in Portland, Oregon. Photo: Steve Wilson/